Butter vs. Margarine - is Butter Better?

For over 50 years we’ve been told to ditch butter in favour of margarine with the aim of reducing saturated fat and raising ‘healthy’ polyunsaturated fats. Multiple recent research studies have turned this theory upside down; instead it appears that sugar, Trans Fats and our excessive polyunsaturated fat intake are in fact much more of an issue. Last month the National Obesity Forum and the Public Health Collaboration issued a controversial report demanding a “major overhaul” of dietary guidelines – in particular, the focus on low-fat diets.

But what’s the real evidence – are there really health benefits of butter or is it all media hype?

Saturated Fat and Heart Disease

The ‘cut down on butter’ approach has its origins in Ancel Key’s Seven Countries Study. In 1958, Ancel  Keys began investigating diet (in particular, dietary fats) and cardiovascular disease. In what is now commonly accepted to be flawed research, Keys found a link between increased consumption of saturated fat and heart disease. However, although data was available from 22 countries, he included only 7 – those that supported his theory. Had he included the full data at the time, he would have shown no correlation between saturated fat and heart disease and we might never have gone down our potentially damaging 50 year margarine and sunflower oil detour.

Keys began investigating diet (in particular, dietary fats) and cardiovascular disease. In what is now commonly accepted to be flawed research, Keys found a link between increased consumption of saturated fat and heart disease. However, although data was available from 22 countries, he included only 7 – those that supported his theory. Had he included the full data at the time, he would have shown no correlation between saturated fat and heart disease and we might never have gone down our potentially damaging 50 year margarine and sunflower oil detour.

As a result we were told to cut saturated fats such as butter, cream, cheese and red meat and increase vegetable oils and low fat products. Yet cardiovascular disease remains the biggest cause of death worldwide (despite mortality rates falling in the developed world due to improved health care and a reduction in smoking) – and the economic cost of heart disease for the UK is estimated to be over £15 billion each year.

And while we’ve been cutting our saturated fats down, obesity and Type 2 Diabetes, both major risk factors for heart disease, have soared:

- Two thirds of British adults are overweight or obese

- One third of our children are overweight or obese

- In the last 20 years diabetes in the UK has doubled – to 3.2 million, and is expected to rise to 5 million by 2025.

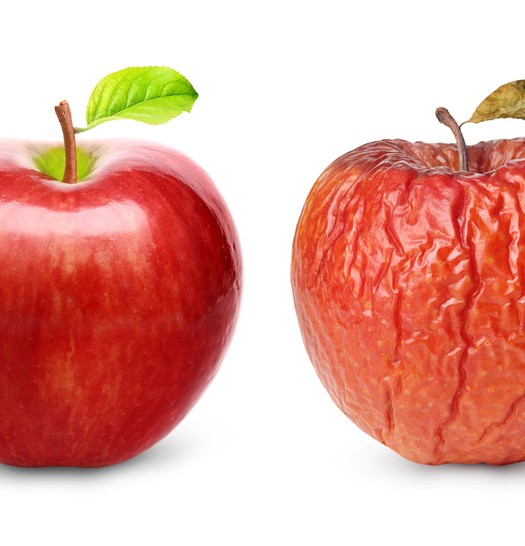

Butter vs. Margarine – which is better?

Margarine: The facts

- It’s spreadable and easy to use (a big bonus)

- It’s dairy-free so suitable for those allergic or sensitive to milk proteins

- It can contain Trans Fats. Margarine was initially (and still is in many countries) made from partially hydrogenated vegetable oils, which are synthetic, chemically altered fats that increase inflammation, alter LDL particle size and raise the risk of heart disease. Trans Fats are not legally required on food labels, but in the UK most big brand margarines don’t contain them any more. However, Trans Fats are still in many processed foods (especially those that use cheap margarine or shortening as an ingredient) and margarines abroad.

- It’s high in polyunsaturated fats (e.g. refined sunflower, corn or soybean oil). Even the ‘olive oil’ margarines don’t really contain much olive oil – only 20% if you’re lucky; the rest are polyunsaturated fats. Polyunsaturated fats are easily oxidised (turn rancid) with processing, or exposure to light and heat (using margarine or sunflower oil for cooking is a bad idea). Eating oxidised fats isn’t good for the body and raises cardiovascular disease risk.

But aren’t high Omega 6, polyunsaturated oils good for us? Yes they are but – this is the important part – only when they’re in balance with other dietary fats. Humans are likely to have evolved on a diet of 1:1 Omega 6 to Omega 3 fats. The Western diet is nearer 20:1 Omega 6 to Omega 3. Upsetting the delicate balance of Essential Omega 6 to Omega 3 fats in the body pushes the body into an inflammatory state; inflammation is a key component of chronic disease, including heart disease, diabetes, cancer, autoimmune conditions and dementia. Our excessive intake of polyunsaturated fats from margarines and vegetable oils is not good for us.

To redress the balance we can test to see our own levels, and then adjust our diet:

- To lower Omega 6 intakes: reduce margarine and vegetable oils

- To raise Omega 3 intake: increase seafood, especially oily fish plus flaxseeds, hempseed, chia seeds, pumpkin seeds, walnuts, seaweed, pasture-fed meat and animal products such as organic milk

Butter: The facts

- It’s a stable fat – meaning that it doesn’t oxidise easily and is great for cooking with.

- It doesn’t impact our imbalanced Omega 6 to Omega 3 ratios. In fact, eating organic butter can actually help the ratio; dairy products from pasture-fed cows contain small levels of Omega 3, the healthy fat CLA, Vitamins A, D and E as well as good levels of the Vitamin A precursor beta-carotene.

- It contains essential fat-soluble nutrients including Vitamins A, D, E and K (grass fed, organic butter has even higher levels). A proportion of the population, myself included, have a mutation in the Vitamin A ‘gene’ meaning we are less able to convert beta-carotene into the ‘active’ form of Vitamin A. The way to get around this is to ‘eat’ retinol – and one of the best sources is butter.

- It’s a good source of Butyric Acid – a beneficial Short Chain Fatty Acid found in butter and ghee that is also formed by bacteria in the small intestine. Sodium butyrate is found almost exclusively in cheese and butter, and has been linked with an improved response to insulin for diabetic patients.

- It’s dairy – so can be problematic for those with milk protein allergies or intolerances. However, using clarified butter or ghee can be a great, healthy option for some people as the milk proteins are removed.

- It contains small amounts of Arachidonic Acid, which can be converted to inflammatory substances called prostaglandins. However eating butter in moderation is unlikely to significantly raise this; more important is to support the anti-inflammatory balance in the body by adjusting overall Omega 6 to Omega 3 intake. In our clinic we use Essential Fatty Acid laboratory testing to accurately measure levels of Omega 3, 6 and Arachidonic Acid in order that we can adjust if necessary.

- It’s hard to spread! We get around this by blending equal amounts of olive oil with butter and storing in the fridge – or simply by leaving small amounts of butter in a butter dish on the counter

The research:

Our understanding of cholesterol has changed in recent years and it’s no longer sufficient to say that saturated fat raises cholesterol levels so we should avoid it. Small, dense LDL cholesterol, not large, bouncy LDL raises cardiovascular risk and saturated fat may actually be beneficial in changing LDL from small dense particles, to the large, bouncy type. It’s the sugar, refined carbs and trans fats, not butter, that raise the undesirable small dense LDL. Most ‘standard’ cholesterol tests give only the total cholesterol picture – that’s why in our clinic we use comprehensive cardiovascular tests that can identify small, dense LDL numbers.

Recent, multiple studies* have found no link between saturated fat and heart disease. In fact researchers in one study found no link between eating more saturated fat and the chances of dying from any cause, dying from cardiovascular disease (heart disease or stroke) or heart disease specifically, or getting heart disease, stroke or type 2 diabetes.

In 2013 unpublished data from the 1970s Sydney Diet Heart Study was reviewed; it was found that those who had replaced butter with margarine had reduced cholesterol levels but actually increased death rates after a heart attack; in short, margarine eaters were actually more likely to die of heart disease.

Other research has confirmed this; there appears to be no cardiovascular benefit of substituting Omega 6 linoleic fats (i.e. margarine and sunflower oil) for saturated fats. In fact, it is increasingly suggested that there is no benefit of a low-fat diet at all – a major study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2013 highlighted that a trial was stopped early due to the overwhelmingly positive results from the participants on the higher fat, lower refined carb Mediterranean diet in comparison to the low fat diet group.

Yet more research found that high fat dairy foods reduced obesity risk, and didn’t raise the risk of heart disease or metabolic syndrome. Some researchers took this a step further and actually concluded an inverse risk between saturated fats from dairy and Type 2 Diabetes and heart disease – in other words the higher the intake, the lower the risk.

In Summary

It seems our grandparents appear to have instinctively known what it’s taken years for researchers to conclude – that a little butter each day isn’t such a bad thing, and may even confer some health benefits. Nutrition research is continually evolving and at Eat Drink Live Well we like to make recommendations based on the latest evidence based research.

In our clinic we don’t always have every client eating dairy. But for those who don’t have a problem with it, we’re generally happy to recommend organic butter and ghee in moderation – alongside other beneficial fats such as Omega 3s, coconut oil, cold-pressed nut and seed oils and olive oil. We suggest zero Trans Fats, and no Omega 6 intake from vegetable oils and margarines; instead we prefer that Omega 6 fats come from natural whole foods such as nuts and seeds.

We hope you enjoy this blog post, let us know your thoughts in the comments below or on social media – we’re on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and Pinterest. And don’t forget to sign up to our newsletter to receive a monthly update of our recipes, nutrition tips and expert advice.

*please contact us if you’re interested in research references